If all the ice covering Western Antarctica has melted, the global level of the sea would have risen 4-5 meters higher, which would cause large floods and problems for communities around the world. This is an alarming scenario, but it happened earlier. Just ask the octopus.

According to a new study, published on Thursday in Science, Octopus Turke, the species of cephalopods living in the southern ocean, were able to move around the melt glacial shield of Western Antarctic 125,000 years ago. This time is key because it is also the last time when the temperature on Earth was in line with the exceptional heat. This may indicate that another free from the ice period in the region may be close, which signals the future collapse of the Western antarical glacial shield.

"Conclusions are concerned because they give very convincing evidence that the Western Antarctic glacial shield becomes unstable and is destroyed when the global temperature rises by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre -industrial and if it is ongoing," said Tim.

"The world is on the way to reaching the climatic target of 1.5 degrees Celsius in the next five years" due to warming due to greenhouse gas emissions, Name, Paleoclimatologist at Victoria University in Wellington in New Zealand.

The Western Antarctic glacial shield has been destroyed several times over the past warm periods in the history of the Earth. These warm periods were caused by the normal fluctuations in the Earth's orbit, which changed the amount of sunlight that falls to the planet for tens of thousands of years, unlike today's global warming caused by man.

Some records indicate that the icy shield naturally collapsed in the last 1 million years, but scientists have not had enough evidence to better determine the time. Now octopus would be their watch.

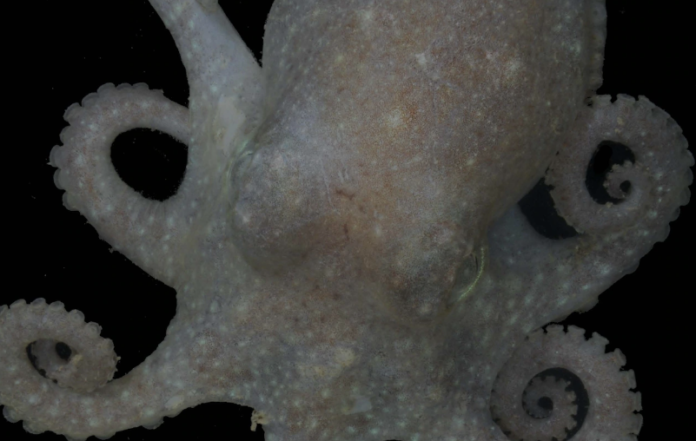

The octopus Turke may not be the most choral animals on the continent, but the small creatures that live on the seabed are inhabited by this region for millions of years. Individuals live only a few years, but their DNA is a capsule of their ancestors.

Like a 23andme test on humans, the team analyzed the genetic material of almost 100 octopus from the South Ocean stored in museums and for research. Some samples were ten years ago and degraded, but the new genetic sequeling technology allowed the team to analyze genomic data with higher resolution than ever before.

The conclusions were unexpected. Octopus, located at a distance of thousands of miles from each other all over the continent - in the seas of Weddell, Amundsen and Ross - were genetically similar. Today, the glacial shield physically divides these seas. Given that Antarctic octopus traveling little, they are unlikely to hike around the continent. So, how did the species branch over such distances?

Using the same types of models to verify past models of people's migration, the team has modeled different scenarios to find out the historical trips of octopus. They launched hundreds of thousands of variations according to scenarios in which the glacial shield was completely integral, partially destroyed and completely destroyed.

One way stood out: octopus traveled with routes between the seas after the Western Ice Shield has completely melted, opening the gaps in the rocks between the regions.

Octopus "found paths [in the sea] to migrate" for generations, said Sally Lau, a leading author of the study and a biologist at James Cook University. "When they migrate, they cross with each other, and [genes] flow from one population to another."

This exchange of genetic metabolism, according to research models, occurred during the last warm period, approximately 129,000 to 116,000 years ago, known as the last interludal age. During the last interludal age, the average global temperature was 0.5-1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than the pre-industrial level. The global level of the sea was 5-10 meters higher than today, and Nanda said that the melt water from Antarctica was probably a big contribution.

Scientists are concerned about the fact that the last interrelose period can be an indicator of what awaits the modern land. Today's global temperature is about 1.2 degrees Celsius higher than the average pre -industrial figure. According to Nesha, without any intended technological solution for removing carbon from our atmosphere, we are "dangerously close to the collapse of the Antarctic Ice Shield", which will continue to increase the global level of the sea over the centuries.

"We are confident that if we keep the warming at the level we feel, the sea level will eventually reach this level," which was observed during the last interrelose period, said Tina de Flierdt, a paleoclymat researcher from the Imperial College of London. "We do not know how fast it will happen."

The sea level is estimated to increase by 30 centimeters by the end of this century, but Van de Flierdt said that an increase can reach 1 or 2 meters if the Western Antarctic glacial shield will be destroyed by warming by 1.5 or 2 degrees.

At the current temperature of the part of the glacial shield of Western Antarctic, may have already reached a turning point. Ice in the Amundsen Sea, where the Taites Glacier of the Judicial Day is already demonstrating irreversible vulnerability to melting. One of the rescue moments is that the area of the glacial shield by the Ross Sea may be less susceptible to melting, said Van de Flierdt.

"The melting in both areas, the Sea of Ross and the Amundsen Sea, would mean the complete collapse of the" Western Antarctic glacier, she said.

Van de Flierdt said the study was "exciting" and was surprised by the authors' confident results in narrowing a period of time up to 125,000 years ago.

An international project called Swais2c will drill to find an old precipitate deposited under the ice. Chemical signatures in rocks can give the key to understanding what happened in the environment at that time, helping scientists to reconstruct the Earth's reaction in the past warm periods.

"The geological past opens a window to the future world, which can be 1, 2, 3 or even 4 degrees," Van de Flierdt said, one of the main scholars Swais2c. Swais2c is designed to study the vulnerability of the Western Antarctic glacier up to 2 degrees Celsius.

"There is no ideal geological counterpart for the experiment that we do with our planet right now," she said. "But the geological past is our best choice to find out how the planet can respond to unprecedented greenhouse gas emissions."